Excerpt from Chapter 7

‘Where are you from?’ I said, since I had to say something. I had no idea what I could converse about with Rahul Kapoor, but we were sitting across a table in a posh, air-conditioned restaurant and after we’d placed our orders, I presumed that some kind of conversation was supposed to take place.

‘New Delhi,’ he said.

Karan was also from Delhi. Cut. N.G. What was the point of going out with somebody else if I kept on thinking about Karan? And anyway, what was the big deal about being from Delhi? Lots of people were. Even Saira was from Delhi.

‘Are you related to the Kapoors?’ I ploughed on with the conversation. ‘To Raj Kapoor?’

‘No, no, not at all. None of my relatives belong to the Hindi film industry.’ Then he added sheepishly, ‘Actually my real surname is Bhanot. I changed it to Kapoor when I came to Bombay because there are so many Kapoors in the industry. It sounds more like hero material, no?’

‘I guess,’ I said wryly. ‘Did your father mind your changing your name?’

‘What does he not mind? He minds my coming to Bombay, he minds my not finishing my graduation, he minds my acting in Hindi films. Especially the Hindi films bit.’

I nodded. If I had a son who left his studies to come to Bombay and act in Jumbo’s films, I would mind.

‘He’s stopped speaking to me since he saw Maut Ke Sikandar.’ Rahul sighed, shook his head and told me, ‘He teaches English literature at Jawaharlal Nehru University.’

‘Oh, that’s the place where there’s all this radical left stuff happening, na?’

‘Not so much nowadays. Things are changing everywhere. Papa’s a hardcore Marxist, though. Completely intellectual. We’re Punjabi, but he only watches films by Bengali neorealist directors. Bimal Roy’s his favourite.’

‘Oh, I love Bimal Roy’s films. Especially Bandini. Have you seen it?’

‘At least twenty times. We had a video cassette at home,’ Rahul said enthusiastically. ‘But his Do Bigha Zameen is a far better film, actually. It’s much more understated.’

‘Understated, hmm.’ I looked at him quizzically. ‘What are you doing here – in Jumbo’s films?’

‘Oh, I love commercial Hindi films. Really I do. From the bottom of my heart. Realistic art films are fine, but they leave you feeling depressed. There’s enough in most people’s lives that gets them down, why should a man go to a theatre and feel even more miserable?’

‘I think that I would feel quite miserable if I had to watch Jumbo’s film for three hours in a movie theatre,’ I said dryly. ‘I much prefer old Hindi films.’

Karan liked Hollywood films, especially sci-fi and… Cut. N.G.

‘But there are thousands, no, lakhs of people out there who spend their hard-earned money to go and see Jumboji’s films,’ Rahul was saying enthusiastically. ‘A rickshaw-wala who earns forty rupees a day pays twenty rupees to sit in a theatre in the evening and watch Jumboji’s film. And he says paisa vasool at the end of it.’

‘But you’re not a rickshaw-wala. Don’t your sensibilities get offended by the inane dialogues and loud costumes?’ I said. ‘You usually wear a white shirt and blue jeans when you come on the set. I’m sure you don’t like the costumes you have to wear.’

‘Oh, you’ve noticed my clothes,’ he said, quite pleased.

‘No, no, it’s just that I’ve been taking care of costumes and continuity, so I notice people’s clothes more,’ I said quickly, then regretted it. It sounded too defensive.

‘I don’t dislike the costumes, actually. They’re dramatic, larger than life. Everything about Hindi films is larger than life. That’s the style, the way the narrative structure works.’

“‘Narrative structure” and all! Does your father say that?’

‘What does my father have to do with this?’ he said, frowning.

He looked very intense, and I suddenly realised that he was attractive. I mean, I’d always known that he was handsome, but it’d had nothing to do with me. Like the verandah of Mehboob Khan’s house on the set, or the façade of the church, his looks gave production value to the film.

‘No, I just thought, since he teaches English Literature at Jawaharlal Nehru University and all…’ I said, my hands toying with the red rose on our table.

‘I’m not quoting his ideas,’ he said huffily. Then relaxed. ‘But you’re right, I must have picked up some of this jargon from Papa.’

‘Which subject were you studying in college?’ I said, plucking a petal from the rose and nibbling it. ‘You mentioned that you didn’t finish your graduation…’

‘Are you very hungry?’ he said, disconcerted.

‘What? Oh, no. Rose petals are supposed to be very good for the eyes,’ I said, offering him a petal. He took it a little hesitantly and ate it.

‘Hey, it’s not bad,’ he said enthusiastically, plucking all the petals off the rose and giving me half of them.

I stole a sidelong glance at the people sitting at the other tables, hoping that nobody had noticed us.

‘You were talking about Hindi films,’ I said with a quick smile, stuffing the rose petals into my purse.

‘Let’s forget about intellectual justifications for why Hindi films are the way they are – the proof of the pudding is in the eating. I was so crazy about movies when I was a kid, that I once stood in a line for five hours to get a ticket for Sholay,’ he told me. ‘I know most of its dialogues by heart. What I wouldn’t do to get Dharamendra’s role in a film like that! “Basanti bhi tayyar, Mausi bhi tayyar. Is liye marna cancel.”’

‘Dharamendra’s cute, but I liked Amitabh more in the film,’ I said. ‘He’s so cool.’

‘Oh, he’s brilliant,’ Rahul said, eyes sparkling. “‘Arre, Basanti se uski shaadi kar ke to dekhiye, ye juwe aur sharaab ki aadat to do din mein chhoot jaayegi.’”

“‘Arre beta, mujh budhiya ko samjha rahe ho,’” I grinned back. “‘Yeh sharaab aur juwe ki aadat kisi ki chhooti hai aaj tak?”’

“‘Mausi, aap Veeru ko nahi jaanti. Vishwas keejiye, woh is tarah ka insaan nahi hai,’” Rahul said, delighted. “‘Ek baar shaadi ho gayi to woh us gaanewali ke ghar jaana band kar dega, sharaab apne aap chhoot jaayegi.’”

‘Actually, I loved Amitabh’s romance with Jaya Bhaduri,’ I said, laughing. ‘He’s quiet, but so romantic, so intense.’

‘You like the strong, silent type, huh?’ Rahul said. ‘No problem, I can also keep quiet.’

He stared deep into my eyes.

If you can’t beat them, join them. ‘Let’s see who blinks first,’ I said flippantly.

We locked eyes over the table. He was trying so hard to look at me seductively, I smiled, but I didn’t blink. He was welcome to think of it as a romantic gesture, there was no way I was going to let him win. Karan had told me once that lovers looked into each other’s eyes to check whether the pupils were dilated because of sexual excitement. Hmm, Rahul’s pupils definitely were dilated, the black almost crowding out the reddish-brown iris. It struck me that perhaps my pupils were getting dilated as well, and I looked away immediately.

‘You blinked first,’ he shouted triumphantly.

‘I did not,’ I said, irritated, looking back at him. ‘I just looked away, I didn’t blink. See, my eyes are still open. I haven’t blinked till now.’

‘I haven’t blinked either,’ he said.

‘You’re lying, I saw you blink when…’ I shut up. This was ridiculous. We were squabbling like kids. How would Kavita and Saira analyse this?

‘You’re a bad loser,’ he said.

I gave him a calm ‘You’re such a kid’ smile.

‘What?’ he said.

‘You were supposed to be proving to me that you can do the strong silent type number,’ I said.

He gave me a sheepish smile and said, ‘Let’s do a second take.’

‘No second takes in life,’ I said, digging into the steaming plate of spaghetti the waiter had served me. ‘You get only one chance.’

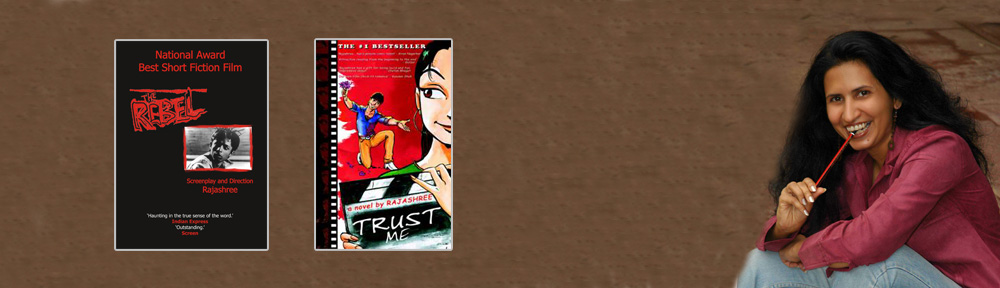

Rajashree

Film-maker & Novelist